Giant, bluefin tuna are built for performance, endurance, and speed. They have been clocked at speeds up to 47 mph. The razor sharp maneuverability and precision locomotion of these powerful fish is made possible by a vascular feature that is unique among animal with backbones: pressurized hydraulic fin control.

Yes, that’s right, tuna use their lymphatic system, a network of fluid-filled vessels and nodes, to control their dorsal and anal fins; their own internal hydraulic system which allows them to turn on a dime when chasing prey (dinner) in the ocean.

Researchers at Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station found that small muscles at the base of the tuna’s fins contract to push lymph/hydraulic fluid into the chamber under the fins, and, from there, into channels in the fins themselves. The fluid then forces the fins into a more erect position. The stiffened fins form a pivot point for the speedy fish, giving them a way to make sharp, quick turns in the water. Imagine the difference between trying to turn a canoe with a pool noodle versus a sturdy wooden oar.

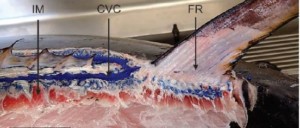

Below is a cross section of a tuna showing the paths (in blue) the lymphatic/hydraulic fluid takes after being propelled by the muscles (in red). IM stands for inclinator muscles, CVC stands for compressible vascular channels, and FR stands for fin rays.

Leave A Comment